Scientists make breakthrough in creating universal blood type

Researchers from University of British Columbia have made a breakthrough in their technique for converting A and B type blood into universal O, the type that is most needed by blood services.

By Erin MatthewsResearchers Peter Rahfeld (left) and Lyann Sim in the lab.

Enzymes in the human gut can convert A and B blood type into O

Half of all Canadians will either need blood or know someone who needs it in their lifetime. Researchers from the University of British Columbia have made a breakthrough in their technique for converting A and B type blood into universal O, the type that is most needed by blood services and hospitals because anyone can receive it.

In a paper published in Nature Microbiology, Stephen Withers and a multidisciplinary team of researchers from the University of British Columbia show how they successfully converted a whole unit of A type blood to O type using their system. They were able to remove the sugars from the surface of the red blood cells with help from a pair of enzymes that were isolated from the gut microbiome of an AB+ donor.

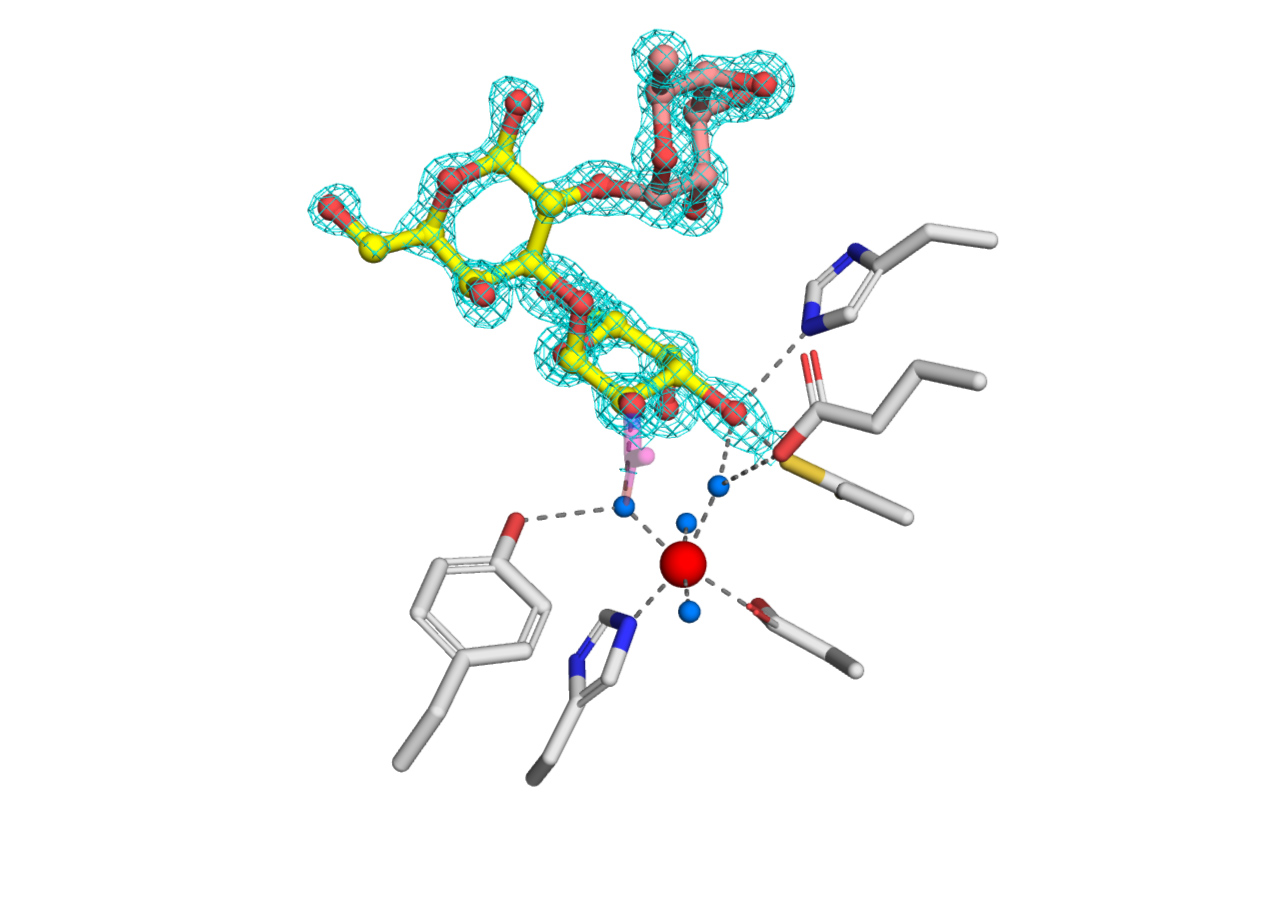

The Canadian Light Source (CLS) at the University of Saskatchewan played a critical role in understanding the structure of a previously unknown enzyme that was part of this pair. The researchers were unable to identify what this unique enzyme looked like from the gene sequence they had. Crystallography, done at the CLS, was crucial for the researchers to understand how this enzyme works and why it had a particular affinity for the A type blood.

The enzyme they isolated didn’t seem to care about the subtypes of A and was faster than previous enzymes used. This means that the researchers can use less of it, making the procedure more feasible in practice.

“Because we can cleave all the subtypes—as far as we can see—and cleave them efficiently… plus, we have taken this enzyme and converted a whole unit of blood and shown that—according to all the measures used by the Canadian Blood Services—it is now type O. It gives us great confidence, but of course there are a lot of safety tests still to be done,” Withers said.

The next step for Withers and his team is to test the safety of the process in greater detail. The researchers are able to do this with a simple test that involves mixing their “converted” blood with other samples to see if there is any antigen-antibody response. This response is similar to how the immune system of a recipient would respond to blood from a donor with the wrong type.

“Two concerns that one would have is that we don’t completely remove the A or that we are causing some other change on the red blood cell surface, though we have no reason to think that at the moment.” Withers said.

Withers noted that the contribution of his team, funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and access to the CLS were all instrumental in the research getting to this stage. While there is a lot of safety testing ahead, this latest discovery brings the researchers closer to their goal of actually converting all blood types to O type blood.

For more information, contact:

Victoria Schramm

Communications Coordinator

Canadian Light Source

306-657-3516

victoria.schramm@lightsource.ca